During my stay with Mehi Mohto’s (fire carried on the head) family this past summer, I reflected on how various events positively shaped my childhood. This period allowed me to gain a new perspective on resilience. An insightful 2017 article from The Atlantic redefined resilience for me: “Current [American] culture thinks of resiliency as gutting it out and getting through, and one foot in front of the other,” the article goes on to state: “But resiliency is learning and making meaning from what happened.” This concept resonated with me, considering my own history and the stories of others who endured childhood trauma. Indeed, while trauma has been a part of my life, it played a smaller role than the positive events in shaping my resilience. I had several positive events that filled the cracks in the foundation created by the generational trauma.

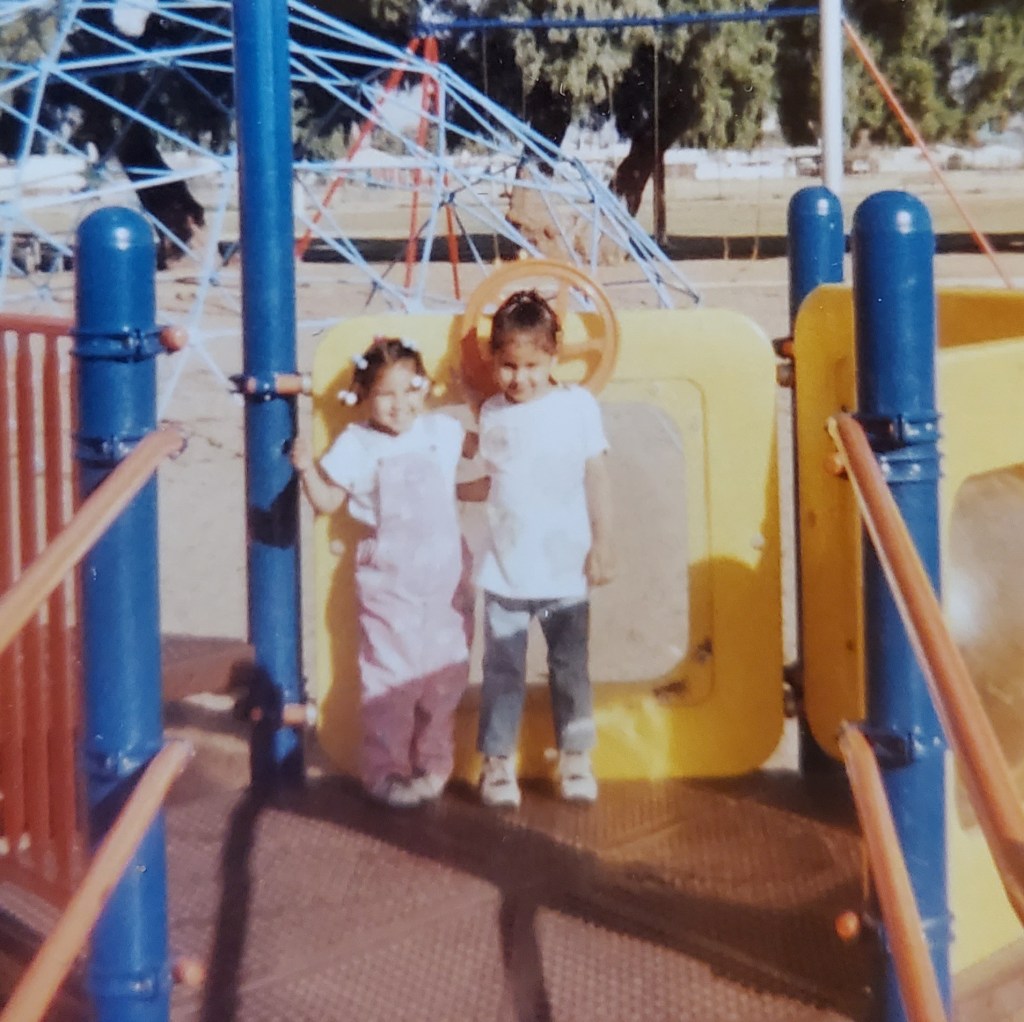

From an early age, I felt responsible for protecting my younger siblings, a situation I described in my subscriber-only posts, “The Unhinged Beast.” However, this sense of duty was actually a form of destructive parentification — a type of emotional abuse where a child becomes the caregiver to their parents or siblings.

My journey hasn’t been without its struggles. Despite my resilience, I faced challenges like a stint with obesity and millennial binge drinking, behaviors shaped by cultural influences, overworking, and my upbringing. Not everyone navigates through such experiences to develop resilience, and I often ponder what set my path apart. This journey of self-discovery began with learning to read, but before diving into that, I need to recount a few pivotal events that impacted my literacy journey before 5th grade.

My reading struggles started a few years before, just after I had started elementary school in a historic African American neighborhood in Phoenix. Ni-oksi waik (my paternal aunt three) would yell at me and occasionally hit me when I struggled with reading, leaving me terrified to read aloud. It didn’t end until Hemako (one) had told our je’e (mother), which resulted in her threatening Ni-oksi waik and anyone else that might think about laying hands on or yelling at us.

Sometime after or around that time, we’d eventually move schools, spending our afternoons with Ni-oksi waik to do our homework. We attended a magnet school, and I ended up with a teacher who compounded the issues I experienced with reading. My teacher, an African American woman whose name I’ve long forgotten, teased me in front of the class daily, referring to me as “the turtle” and making fun of me for reading slowly, messing up words, and not speaking loud enough. Her classroom wasn’t a safe place for me. I felt comforted only by the sympathetic teacher’s aide, an African American woman, who was gentle and amused by mistakes over public ridicule and bullying.

The standardized tests also often took place in the morning when I was still tired from the nightmares I experienced during those times, leading to more academic anxiety. I suffered from recurring nightmares and bed-wetting until just before puberty. A sign often related to early childhood sexual abuse (which I’d kept secret until just after turning 30) that I was punished and ridiculed for. My difficulties in school were not due to a lack of intelligence or effort but stemmed from the emotional and psychological burdens I carried.

These experiences instilled in me a fear of being wrong, driving a rigid need for perfection once I did learn to read. The adults around me, both at home and school, failed to recognize the root causes of my struggles. I don’t recall anyone caring to ask why. I was behind, and their objective was to catch me up. The school, upon testing, had no inclination to pry deeper into what was wrong other than improving my test scores. The slew of English as a second language and special education classes proved to be mostly fruitless, as I’d show little growth in reading by the end of 4th grade. I wasn’t dyslexic, and I wasn’t learning English as a second language; I was traumatized and stressed out by my environment. My literacy issues had nothing to do with my ability to learn and everything to do with my self-confidence and anxiety as a nine-year-old.

I needed tools and resources I could use and a place to grow in confidence safely as I quietly carried more weight on my shoulders than the average adult. My experiences left me feeling constantly surrounded by physical and emotional threats. It was around this time I also developed suicidal ideation from these experiences. I longed to be saved and protected from the world that I was in, and the only thing people cared about was that I couldn’t read.

Children are often silent witnesses to adults’ actions and subsequent reactions and lack the coping skills to navigate complex questions without clear and gentle guidance. The consequences of adult actions, even things that aren’t as extreme as child abuse, can have devastating effects later in life. It may appear in unexpected ways, as I’ve learned recently while listening to Ramit Sethi’s podcast, a man I believe can help teach people how to change their lives through financial literacy. Check him out! He teaches people “How to Live a Rich Life.”

Now, as I reflect on those times, I understand that resilience is shaped early in life and is heavily influenced by the coping mechanisms we’re taught and the stability of our foundations. Emotional intelligence, I believe, is as crucial as academics, if not more so. My journey to overcoming these challenges began with the interventions of people like Ni-kahk (my paternal grandmother), who, without prying into the specifics of my issues, helped me overcome my fear of reading and tests.

As I share these parts of my story, I do so with the hope of shedding light on the complexities of childhood trauma and its long-lasting effects. In my next post, I’ll delve into the turning point in my literacy journey and Ni-kahk’s role in it.

Key Lessons and Takeaways:

Here are five things I hope you learned from this post:

- Resilience is more than endurance; it’s learning and finding meaning in our experiences.

- Childhood trauma can profoundly impact learning and development, often manifesting in unexpected ways.

- Emotional intelligence and understanding are crucial in helping children navigate their challenges.

- Supportive interventions from caring adults can significantly alter the trajectory of a child’s life.

- Sharing our stories can illuminate the complexities of trauma and inspire others in their journeys of healing and growth.

You can report suspected child abuse here or call 800-422-4453. No child should ever be abused or neglected.

If you find this blog compelling, helpful, or valuable and have the means, please consider donating. Your support would be greatly appreciated. Thank you for joining me on this journey.

AI transparency and ethics note: This blog has been reviewed and edited with the assistance of Chat GPT-4 technology to enhance punctuation, grammar, and readability.